Fantastic Friday: My Parents, My Past

Today I’ll be presenting at Longwood University’s Summer Literacy Institute. One of my presentations is an “about me” author discussion in which I take the audience through my dual life as writer-teacher as well as journey through my past to take a look at my influences. In preparing the presentation, I realized that serendipity, or fate, does play a role in our lives. Sometimes, when we aren’t sure whether we’re in control, factors are pushing us toward our destiny.

Whether they realized it or not, my parents created the perfect mix in an environment that fostered creativity yet kept me on edge just enough to encourage the desire to write.

First, my mom:

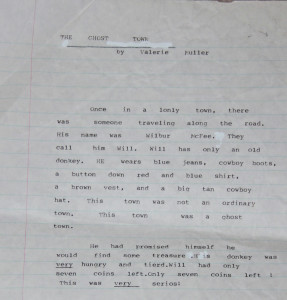

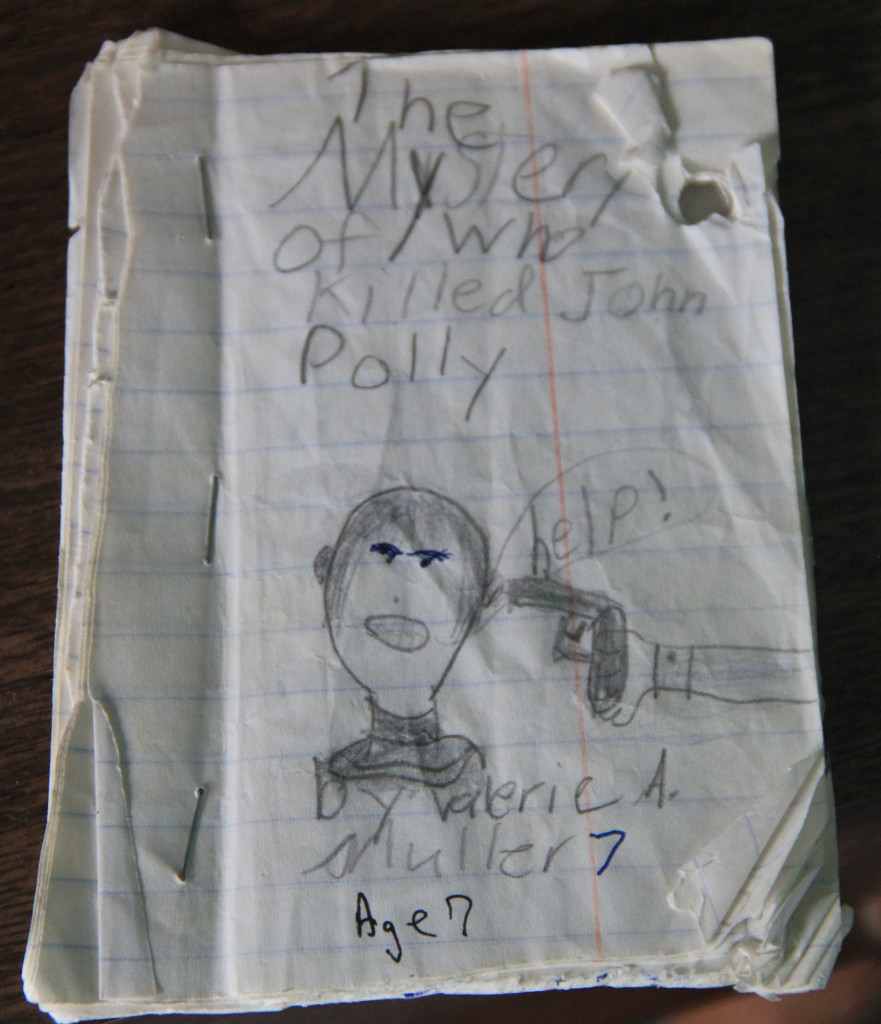

One of the first things I remember about my mom and reading/writing is admiring how neat her handwriting was (and still is). It was almost like artwork, the way each letter was shaped consistently. It almost looked like a computer font. Try as I may, I never could (and still cannot) write that neatly. But my fascination with the way letters form on a page has stayed with me. To this day, I write by hand the same way I used to as a kid, only typing the second (or subsequent) draft.

Mom also read to me all the time, fostering my love of reading and stories—something essential to any writer.

Something else about my mom: she was the voice of reason, the stable rock, of my childhood. She went out of her way—sometimes to a fault—to explain everything to me. If she had to run to the store, she would explain exactly where she was going, why she was going, and how long she would be gone. She was always right almost to the minute. Because of her diligent way of explaining things, I always assumed the world contained a sense of logic.

Enter my dad.

My dad is a logical person, but he did not make the same effort to explain things logically to me—except when it came to tools, which could be dangerous, of course. He explained, for instance, that saws could cut skin, fire could burn, and hammers could bruise. But other than that, he liked to have a little fun. Talking about my dad in college, one of my professors said he is “a writer’s gold mine.” And it’s true. The weird, creative stories he told me definitely made an impact.

As a kid used to Mom’s sense of logic and truth, I could not fathom the fact that a parent would “fib” to a child. So when my dad told me “stories,” I believe him.

First: a child will turn to stone if she is awake past midnight. It had to do with trolls who use the power of the moon. I’m sure he told me this as incentive for me to go to bed early, but all it ended up doing was making it harder for me to fall asleep. Who can sleep when they have to constantly check the clock and make sure they aren’t turning into stone? I mean, I would literally sit in bed and wiggle my toes just to make sure the stone-spell wasn’t setting in.

My uncle walks with a cane. But when he would stay at our house at night, he wouldn’t use the cane to get from the couch to the kitchen or the bathroom. I asked my dad why. Instead of logically explaining that he didn’t need a cane for short distances, my dad made up this whole tale: that I only saw my uncle without a cane at night, at night the moon is out, another word for “moon” is “lune,” and my uncle can be pretty “looney” sometimes; hence, he used the power of the moon to be able to walk without a cane.

My younger sister rolled her eyes.

I was fascinated. Who would have thought such power existed in the world? How amazing! If only I could harness some of that magic.

My dad’s crazy stories fostered my sense of wonder. After watching The Dark Crystal and noting that female gelflings have wings, I would check the mirror on the back of my door each morning to see if my wings had sprouted yet. No joke.

My mom loved the TV show Beauty and the Beast. Always loving a good joke, my dad told me that Vincent, the lion-man, was really my father. He had to leave me “with the humans” for a while, while he sorted things out. But he was my father and Catherine, the female human lead in the show, was my mother. He even said, in Catherine’s voice, “Oh, Vincent, she has your hair,” explaining that the only way I could have red hair—when Dad had brown and Mom had very dark brown—was that Vincent was actually my father.

My dad laughed at this tale, and once again my younger sister rolled her eyes. He had no idea that I took it seriously. I was terrified to go up to my room at night: I had to enlist my younger sister to go into my room first and turn on the light to make sure Vincent wasn’t there waiting for me. And even if it was safe, there was no telling when Vincent might hop up onto the roof and climb in through the window. He was stealthy that way. And if he arrived after midnight and woke me up—well, then he would have a stone statue of a child.

So much to worry about!

Yet so much to foster the imagination.

I like to think I’ve grown up a little since then—I no longer fear that Vincent will come for me. But I haven’t lost that sense of wonder about the world. Sometimes at work I’ll share my irrational fears with coworkers. “Hey, have you ever gotten to work and had to look down because you worry that maybe you forgot to put on pants, or a shirt, or shoes?”

Their reactions show me just how abnormal my thoughts are. But that’s the thing: I’m always thinking of strange—but slightly possible—possibilities. When an earthquake hit our building and my coworkers were trying to figure out what was happening, my brain already accepted that not-so-abnormal possibility and had my legs running into the door frame before the rumbling was over. I even had time to decide whether it would be smarter to stay there or make a run for the exterior door (I stayed).

The point of all this is: my mom’s sense of logic and my dad’s warped sense of creativity fostered the perfect atmosphere for the creative person I would become. My mom’s love of writing and reading made it a logical, calming activity. My dad’s sense of creativity left me with that edge that is never truly content with the world as it is. Combined, it’s the perfect storm for a writer.

The first time I remember words coming together to create true, resonating meaning: My dad had been reading “The Night Before Christmas” with me for weeks and months to the point where I nearly had it memorized. I knew the story and understood what was happening, but it wasn’t until one particular moment that the words resonated with me. It was a snowy Connecticut winter, and one night my dad approached. He reminded me of the line from the poem “The moon on the breast of the new-fallen snow,” and then he pointed out the dining room window. The snow had fallen and sat undisturbed on the lawn. In the moonlight, it sparkled as if fairies had sprinkled dust all over. Indeed, looking out, it was almost as if the midday sun were shining on everything. It was the first time I understood that words could not only paint mental pictures but could also evoke emotions. I realized that whenever I read that line from the poem, even if I was reading it from a tropical island, I would be summoned, at least emotionally, to that moment—to the snow sparkling under the moonlight. What a beautiful image.

The first time I remember words coming together to create true, resonating meaning: My dad had been reading “The Night Before Christmas” with me for weeks and months to the point where I nearly had it memorized. I knew the story and understood what was happening, but it wasn’t until one particular moment that the words resonated with me. It was a snowy Connecticut winter, and one night my dad approached. He reminded me of the line from the poem “The moon on the breast of the new-fallen snow,” and then he pointed out the dining room window. The snow had fallen and sat undisturbed on the lawn. In the moonlight, it sparkled as if fairies had sprinkled dust all over. Indeed, looking out, it was almost as if the midday sun were shining on everything. It was the first time I understood that words could not only paint mental pictures but could also evoke emotions. I realized that whenever I read that line from the poem, even if I was reading it from a tropical island, I would be summoned, at least emotionally, to that moment—to the snow sparkling under the moonlight. What a beautiful image.

And I don’t even like snow!

But I think from that moment, I was hooked. I understood the power of words, and I needed an outlet for all that creativity. It would be impossible, from that point forward, for me not to be a writer.

Leave a Reply