Fantastic Friday: A Trip to the Newseum

Earlier this month, I got to chaperone a high school field trip to the Newseum, and the experience stayed with me. I thought I’d share some highlights.

(Because I was chaperoning a class on media ethics, I did not view the museum in order (top floor to lowest floor). Rather, I visited in order of my own preference, since I knew I wouldn’t have time to see everything.)

Overall, the museum reminded me of why I’m a writer and why I’m involved with Freedom Forge Press, an organization dedicated to sharing stories of freedom with the world. Moments in human history are easily lost and forgotten over the generations. But with the help of media and art, younger generations can be reminded of the struggles that came before and hopeful gain insight.

There are boxes of tissues available throughout the museum, and from my observations, they are well-used. Many of the exhibits are quite poignant.

First, a piece of the Berlin wall. The exhibit was set up to show the difference between freedom of expression and… its opposite. This view of the wall came from the western side of the wall. When I crossed over to see the side that faced East Berlin, there were no markings whatsoever. A complete repression of human expression.

This is contrasted with an exhibit about the American Revolution, the spirit of which was in stark contrast to repressive governments.

Indeed, the museum emphasized the importance of a free press in helping to inform the people.

Indeed, the museum emphasized the importance of a free press in helping to inform the people.

On display: a printing press. The amazing thing is, we all have printing presses in our pockets nowadays.

The museum featured important elements from stories of national interest, including an FBI exhibit and details about the Unabomber. Most of the displays, save perhaps the feature on JFK and his family, were uncomfortable–but in a thought-provoking, life-changing way.

For instance: on display was a huge antenna from atop the toppled building on 9/11. There were also several partially-destroyed electronics, wallets, and other artifacts left by the victims of the attack. The museum featured a video on 9/11, but I could not bring myself to visit (especially given that there was so much more I wanted to see). Having lived through it, the memories were still fresh. But I was heartened that most of my students chose to view the video, and they were still talking about it in school afterwards. After all, they were barely born in 2001 (some of them weren’t yet), and none remember the attack personally. The museum had already served part of its purpose in educating and inspiring another generation to realize the gravity of all that came before.

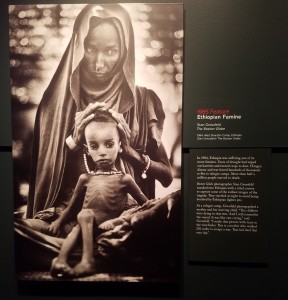

The exhibit I wanted to see the most was the Pulitzer Prize photography. I had expected it to be powerful, but I completely underestimated what I would encounter. The room was silent, and several people were in tears. Two pictures stood out to me especially, though there were plenty that touched me. In this famous picture by Stan Grossfeld, an Ethiopian mother holds her starving child after walking 250 miles to seek refuge. The photographer noted that he took “that picture with tears in the viewfinder…. The kid died that very day.”

The exhibit I wanted to see the most was the Pulitzer Prize photography. I had expected it to be powerful, but I completely underestimated what I would encounter. The room was silent, and several people were in tears. Two pictures stood out to me especially, though there were plenty that touched me. In this famous picture by Stan Grossfeld, an Ethiopian mother holds her starving child after walking 250 miles to seek refuge. The photographer noted that he took “that picture with tears in the viewfinder…. The kid died that very day.”

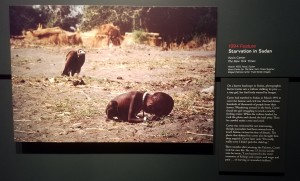

Anotherpicture is equally tormenting. The photographer, Kevin Carter, was in Sudan, taking pictures of a girl nearly starved to death, with a vulture waiting in the background. Like the other journalists, Carter had been told not to touch any famine victims because of the fear of disease spreading. Following that warning, he watched her, took the picture, and then chased away the bird. After taking the picture, he crawled under a tree and cried. Although he won the Pulitzer, he was criticized for not helping the girl, and he said it was a regret of his. Three months after winning the award, he committed suicide.

Anotherpicture is equally tormenting. The photographer, Kevin Carter, was in Sudan, taking pictures of a girl nearly starved to death, with a vulture waiting in the background. Like the other journalists, Carter had been told not to touch any famine victims because of the fear of disease spreading. Following that warning, he watched her, took the picture, and then chased away the bird. After taking the picture, he crawled under a tree and cried. Although he won the Pulitzer, he was criticized for not helping the girl, and he said it was a regret of his. Three months after winning the award, he committed suicide.

This was a picture discussed in the media ethics class. What about those who argued that Carter should have helped the girl? While there is no “right answer” for what to do in such a situation, the message that came out of the visit to the Newseum was that despite the suffering of that one child, the work Carter did on that photograph helped to raise awareness of issues in Sudan—as other disturbing photographs help raise awareness about problems across the world. We are each only one person, but our voice has the power to resonate with others–dozens, hundreds, thousands of others. I still adamantly believe that honest and open communication is the best way to effect change in the world.

This was a picture discussed in the media ethics class. What about those who argued that Carter should have helped the girl? While there is no “right answer” for what to do in such a situation, the message that came out of the visit to the Newseum was that despite the suffering of that one child, the work Carter did on that photograph helped to raise awareness of issues in Sudan—as other disturbing photographs help raise awareness about problems across the world. We are each only one person, but our voice has the power to resonate with others–dozens, hundreds, thousands of others. I still adamantly believe that honest and open communication is the best way to effect change in the world.

The Pulitzer Prize room included several celebratory photographs–such as athletes celebrating at the Olympics–as well as many even more disturbing photos. The room remained somber. After that, I stopped at the exhibit on presidential dogs since I needed something a bit happier to end my trip with.

Perhaps my favorite exhibit was one I saw midway through my trip. There is a huge room with archives of historic newspapers, and by walking through the timeline backwards, I was able to revisit significant events of my lifetime as well as take a look at what previous generations would have seen:

I’ve written before about the Svalbard Global Seed Vault and the message of hope that is there, despite the grim undertone of saving seeds for use after a global disaster. To me, the archives of noteworthy newspaper headlines is similar: if we remember the past, we can celebrate our victories and see how far we’ve come, and perhaps we can learn from the mistakes of those who have come before.

I’ve written before about the Svalbard Global Seed Vault and the message of hope that is there, despite the grim undertone of saving seeds for use after a global disaster. To me, the archives of noteworthy newspaper headlines is similar: if we remember the past, we can celebrate our victories and see how far we’ve come, and perhaps we can learn from the mistakes of those who have come before.

The Newseum is worth a visit if you’re in the area: anything that encourages self-reflection and reflection on our place in the world can help an individual become a more thoughtful citizen. And that’s how you make the world a better place–one conscience at a time.

Leave a Reply